On this day in 1658, surgeon and noted lithotomist Thomas Hollier operated on Samuel Pepys’ bladder stone. The operation took place in Pepys’ cousin Mrs Jane Turner’s house in Salisbury Court, the street on which he had been born 25 years before. Pepys had long suffered the discomfort and frequently extreme pain of ‘the stone’ when he decided that as its debilitating effects could only worsen, he would submit himself to the dangers of the operation, pre-anaesthetic. Lithotomy was a longstanding but specialised branch of surgery, and Pepys’ chose a man with highly regarded skills.

Hollier performed a number of lithotomies that day, and being first on the list worked in Pepys’ favour in an age when the control of infection was not well understood or managed, for Hollier’s hands and instruments were as clean as they would be. Luckily for Pepys and for posterity the operation proceeded safely. Pepys’ biographer Claire Tomalin describes in detail the lengthy preparations to ready lithotomy patients, with prescriptions for specific food and drink, advice to “cultivate a calm frame of mind,” to trust the surgeon, and to talk with a religious adviser on the day itself.

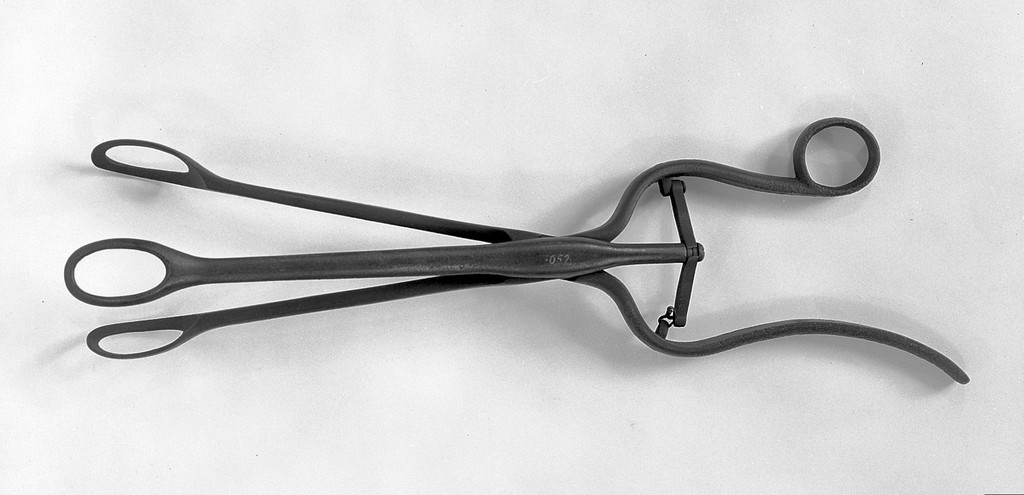

Pepys would have been bound fast to a table with padding to position and make him more comfortable, then held by strong men, while “the surgeon lubricated his instruments with warm water and oil or milk of almonds: the catheter, the probe, the itinerarium, the specular, the pincers, small hooks and so forth; he also had powder to stop bleeding, sponges and cordial waters to hand.”

The itinerarium was passed through the urethra into the bladder to find the stone and guide the knife, which was used to make an incision through the perineum and into the bladder: “The patient’s face was sponged as the incision was made. The stone was sought, found, and grasped with pincers; the more speedily it could be got out, the better. Once out, the wound was not stitched…but simply washed and covered with a dressing, or even kept open at first with a small roll of soft cloth known as a tent, dipped in egg white. A plaster of egg yolk, rose vinegar and anointing oils was then applied. Pepys, no doubt by now fainting with shock and pain, was unbound and moved to his warmed bed.”

With bed-rest and a further regime of soothing drinks and anointments, plain diet and changing of dressings, Pepys’ recovery from the operation took thirty-five days and was deemed a success. Pepys had a commemorative case made for his stone – considered to be of great size – after its removal, and held an annual celebration of his successful lithotomy. He also became friends with Hollier, referred to in his diary as ‘Holliard,’ who continued to treat Pepys and his wife.

Thomas Hollier (1609-1690) was apprenticed to surgeon James Molins (c.1580–1638, Master 1632), made free of the Company in 1637, chosen for the Livery in 1639 and became Master in 1673. Hollier’s second wife Lucy was Molins’ granddaughter. Hollier was appointed surgeon for scald heads at St Thomas’s Hospital in 1638, beginning 53 years of service there. When James Molins’ Royalist son Edward (who had succeeded all his father’s appointments at St Thomas’s) joined King Charles I army in 1642, Hollier, a staunch Parliamentarian, deputised for him. In 1644 the House of Commons ordered the dismissal of Molins and appointed Hollier in his place as surgeon and surgeon for the stone. By the time of Pepys’ operation in 1658, Hollier was a celebrated lithotomist, with 40 patients treated successfully the previous year, and an appropriate choice for Pepys’ own procedure.

A visit by Pepys to the Creechurch Sephardi synagogue in December 1659 served as a poignant reminder that however skilled the lithotomist, survival was far from guaranteed; the occasion was a memorial to the synagogue’s founder, and ally of Oliver Cromwell, Antonio Ferdinando Carjaval (c.1590-1659), who had been cut for the stone the year after Pepys, also by Hollier. Pepys wrote of the occasion in a letter to his patron Edward Montagu:

“Being this morning (for observacion sake) at the Jewish Synagogue in London I heared many lamentacions made by Portugall Jewes for ye death of Ferdinando ye Merchant, who was lately cutt (by the same hand wth my selfe) of ye Stone”

Further reading:

- A portrait of Thomas Hollier, Pepys’s surgeon, G C R Morris MA DM MRCP. Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons of England (1979) May;61(3):224-9. (online article)

- The stonecutters of 17th Century London, Jonathan Charles Goddard. Urology News Volume 19 Issue 5 July/August 2015. (online article)

- The History of Urinary Stones: In Parallel with Civilization, Ahmet Tefekli and Fatin Cezayirli, ScientificWorldJournal. 2013; 2013: 423964. (online article)

- Pepys’ Diary entry for 26 March 1660, commemorating his being ‘cut for the stone’

- Tomalin, Claire. (2002) Samuel Pepys: The Unequalled Self. London: Viking